In this section, we will study how does the Laplace transform behave when we shift the function f(t) on the t-axis and when does F(s)=\mathscr{L}\{f(t)\} shifts on the s-axis.

1. Unit step function and time shift description

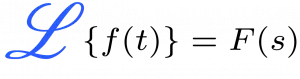

We define the unit step function as

u(t-a)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & 0\leq t<a \\ 1, & t\geq a \end{array}\right.

which is also known as the Heaviside function. The graph of u(t-a) is given below:

The importance of the unit step function lies in the case f(t) on the differential equation:

ay''+by'+cy=f(t)

is discontinuous at one or more points.

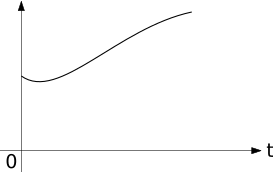

In fact, let f be a piecewise definied as follows:

\displaystyle f(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & 0\leq t<a \\ g(t), & t>a \end{array}\right.

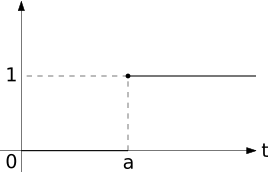

If the graph of g(t) is:

Then f(t) is represented by the curve below. And we can rewrite f using the unit step function, i.e,

f(t)=g(t)u(t-a)

2. Time shift theorem

Considering a function f(t) defined on the variable t\geq0, then

f(t-a)u(t-a)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & 0\leq t<a \\ f(t-a), & t\geq a \end{array}\right.

i.e., f(t-a)u(t-a) is the function f transladed a units to the right on the t-axis.

Proof:

From the definition of the Laplace Transform, we have

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\}=\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t-a)u(t-a)dt

Since 0<a<\infty then:

\displaystyle\int_{0}^{\infty}=\int_{0}^{a}+\int_{a}^{\infty}

i.e.,

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\}=\int_{0}^{a}e^{-st}f(t-a)u(t-a)dt+\int_{a}^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t-a)u(t-a)dt

But as

u(t-a)=0,\qquad 0\leq t<a

so the first integral is equal to zero. Also,

u(t-a)=1,\qquad t>a

gives us

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\}=\int_{a}^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t-a)dt

Now, let u=t-a\Rightarrow du=dt. In the boundaries:

\begin{aligned} & t=a\to u=a-a=0 \\ & t=\infty\to u=\infty-a=\infty \end{aligned}

Therefore,

\begin{aligned} \mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\} & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-s(u+a)}f(u)du \\ & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-su-as}f(u)du \\ & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-su}e^{-as}f(u)du \end{aligned}

The term e^{-as} is constant in respect to u, thus

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\}=e^{-as}\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-su}f(u)du

and by definition

\displaystyle\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-su}f(u)du=F(s)

Hence

\mathscr{L}\{f(t-a)u(t-a)\}=e^{-as}F(s)

Example 1:

Calculate the Laplace transform of (t^2-4t+4)u(t-2).

To evalute \mathscr{L}\{(t^2-4t+4)u(t-2)\}, observe that

t^{2}-4t+4=(t-2)^{2}

and if f(t)=t^2, then (t-2)^{2} represents f shifted 2 units on the t-axis. Also

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{f(t)\}=\mathscr{L}\{t^{2}\}=\frac{2}{s^{3}}

Thus, for a=2 in the formula above, we have

\begin{aligned} \mathscr{L}\{(t^2-2t+4)u(t-2)\} & =\mathscr{L}\{((t-2)^{2}u(t-2)\} \\ & =\mathscr{L}\{f(t-2)u(t-2)\} \\ & =e^{-2s}F(s) \\ & =e^{-2s}\cdot\frac{2}{s^{3}} \end{aligned}

3. Frequency shift theorem

The first shifting theorem works with the translation of the function f on the t-axis. In this section, however, we study the translation of F(s)=\mathscr{L}\{f(t)\}.

Proof:

From the definition

\begin{aligned} \mathscr{L}\{e^{at}f(t)\} & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-st}e^{at}f(t)dt \\ & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-st+at}f(t)dt \\ & = \int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-(s-a)t}f(t)dt \end{aligned}

To conclude it, note that when the exponent of the kernel is -st, i.e,

\displaystyle\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t)dt

then

\displaystyle\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t)dt=F(s)

Hence, as the exponent is -(s-a)t, we have

\displaystyle\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-(s-a)t}f(t)dt=F(s-a)

Therefore,

\mathscr{L}\{e^{at}f(t)\}=F(s-a)

The function F(s-a) represents F shifted a units to the right, if a>0, on the s-axis or a units to the left in the case a<0.

Example 2:

Calculate the Laplace transform of e^{3t}\cos(t).

As the Laplace transform of f(t)=\cos(t) is

\displaystyle F(s)=\frac{s}{s^{2}+1}

then

\mathscr{L}\{e^{3t}\cos(t)\}=F(s-3)

because a=3 and f(t)=\cos(t). Thus

\displaystyle\mathscr{L}\{e^{3t}\cos(t)\}=\frac{s-3}{(s-3)^2+1}

We reached the end of this short lesson about the Laplace transform of time (frequency) shifted functions. For a full list of Laplace transform properties, check this post!